This post is also available in: Macedonian French Spanish German Russian

Aco Šopov’s Legacies*

by Kata Ćulavkova

I have written about Aco Šopov’s poetry on several accounts. On one occasion I was interpreting his poem ‘Nonbeing’ (The Term Nonbeing or the Creative Drive, 1983), on another occasion I was construing his poem ‘The Word’s Nativity’ (Interpreting Circle, 2005), another time I prepared an essay on the harmony between sound and meaning in his poetry (The Primordial Drama in Aco Šopov’s Poetry, 1993), and I also wrote an extensive study, a foreword to the selection of his poetry, published by Makedonska kniga from Skopje. This foreword is titled The Song’s Maturity or an Attempt to Reconstruct the Developing Creative Principles in Aco Šopov’s Lyrical Poetry (1993, VII-XLII). I have also written a comparative study of Aco Šopov and Léopold Sédar Senghor’s oeuvres, for an international conference held in Skopje (2006), then in relation to his poetry collection Tree on the Hill published in 1980, and finally, I have also written about his oeuvre indirectly, on account of the monographic study by Jasmina Šopova on Šopov (Aco Šopov: Quests and queries, 2002), as well as the specific selection and presentation of the poetics of Senghor and Šopov (Senghor and Šopov side by side, 2006), an edition published in two languages, Macedonian and French. I would also like to mention the many speeches and interpretations of Aco Šopov’s poetry that I have done during my graduate and postgraduate studies (mainly interpretations of his poems from the cycles on nonbeing and the black sun, particularly his miniatures. One of these (Fishing by the Lake) was included in my thesis titled The Features of Lyrics (1988).

Why am I writing about all of this? Why such an introduction and a self-promotional retrospective of my interpreting experiments? The answer will be closest to the truth if I say that I would like to avoid repetition, working on this selection of Aco Šopov’s poetry. This was the reason I abandoned the idea to prepare a collage of my own views on Aco Šopov’s poetry. I can undoubtedly say that this time I feel the urge to present Aco Šopov’s oeuvre from a different perspective. This new perspective derives from the current post-Šopov constellation of Macedonian poetry. This perspective enables us to actually place value on the matter that is interpreted. Besides Šopov’s poetry, this perspective enables an emphasis on the overall corpus of contemporary Macedonian poetry, particularly that from the post-war period, concluding with 1980, which encompasses Macedonian Modern. Such a dual perspective implies a strategy for comparative assessment of the developmental and systematic principles of Šopov’s poetry in the context of contemporary Macedonian poetry, which is why I will abandon the technique of close reading of certain texts by Šopov, or the sustained interpretation of his oeuvre from an inner point of view. This methodological variation imposed itself as significant in determining Aco Šopov’s role (speaking stereotypically) in the system of Macedonian literary and cultural values. It is logical to do this now, since Šopov’s poetry has already attained the attribute of an undoubtedly valuable legacy, and Aco Šopov can be considered as a Macedonian classic, along with the oeuvres of several prominent authors such as Blaže Koneski and Slavko Janevski, for instance.

With this comparative interpretation of Aco Šopov’s poetry and contemporary Macedonian poetry I focused on the most active period of Šopov’s creative oeuvre along with the corpus of contemporary Macedonian poetry, which covers the period between 1944 and 1980. This period, although often seen as introductory to contemporary Macedonian literature, that is the period of establishing and stabilising the identity of contemporary Macedonian post-war literary and linguistic expression, represents much more than a simple introduction into a new linguistic and artistic canon. Kosta Solev Racin and Kole Nedelkovski had the role of introducers and founders of contemporary Macedonian literature to a greater extent than the Macedonian trio from the first post-war generation, Koneski, Janevski and Šopov, who entered into an already prepared territory, at least initially. My intention with this is not to reduce the value of the founders of the contemporary Macedonian literary tradition, but on the contrary, I would like to underline that they are much greater founders, for various reasons. Namely, the period of linguistic, poetic and aesthetic disorientation with Aco Šopov is relatively short. During this short period Šopov overcomes the delusion that he should write in the Serbian language or that he should stay in the positions of the revolutionary, patriotic and social poetics. Perhaps thanks to the rapid and intense turnabouts that occurred in the social and cultural context, perhaps by interaction of other phenomena whatsoever, the thing that matters is Aco Šopov’s fast recovery from the period of patriotic pathos and the identification of his lyrical object, subject and code with the hymns from the end of World War II and the first years of the establishment and functioning of the socialistic regime and the revolutionary spirit, covered with a collective overtone. Moreover, Aco Šopov, even in his earliest phase, shows a strong individual impetus. This impetus is so strong that it opposes all the governing stylistic and thematic conventions. How else can we explain his first anthological poems ‘Love’ and ‘Eyes’? How to deny the fact that, judging by these two poems, even in the earliest phase of Šopov’s oeuvre, which evolved during the period when Macedonian literature was governed by the partisan and revolutionary kind of social and patriotic poetry, we are dealing here with avant-garde deviations from the governing aesthetic conventions? How can we disregard the realisation that, even in the earliest poetry by Šopov, in relation to the collectively intoned voice of the epoch and worldview, there is a highly sensible and personal linguistic contact with the world? In this linguistic contact with the world, Šopov’s oeuvre experiences several poetic canons: the canon of futurism (in his marches and hymns) and of expressionism, merged in a hybrid dominated by the specific Macedonian, anti-fascist revolutionary and social strife (‘On Gramos’); the canon of oral poetics rooted in the linguistic and cultural tradition, which echoes with its recognisable stylistic schemes and stereotypical moments (‘The Death Note of a Partisan’, ‘Partisan Spring’); the anti-conformist mix of various canons (‘Kratovo’). Šopov, in this period, is in dialogue with the time in which he lives and creates. The key poetic interests and turnabouts are reflected in his poetry, which are typical for Macedonian poetry in general. The same thing happened to other poets of the time, with the sole difference that not everyone had the talent and power to separate from the whole as a special individuality (authentic style, language and worldview).

Then we have the encounter of Šopov, the poet and the lake (1952). With the Lake of Life and Death. With the God of language. This is the time of the coded, hermetic speech. This is the time of the multiplied semantic mainstream. The Sphinx of poetry. Not a hole to peep through. A metaphor. A rebus. A riddle. Life and death, being and nonbeing become a recognisable theme that forms the key poetic world of Šopov, the shadow of death, birth seen as dying, and life as facing the irreversible. This apparently general philosophical world is transformed into specific poetic visualisations by Šopov, into linguistic images and figures, into symbols and harmonies, which can be illustrated with the image of daydreaming by the lake shore, with the numerous poeticised images of the lake, with the parables of the poem and poetry (‘The Song’, ‘The Poet and the Love’). The poem becomes the home of sorrow and joy, a poetic metathesis of the ambivalent sense for the home (language, tradition). The verse becomes a parable of existence, of being, of the essence. Verse is also a way of acting. Verse is a revelation. The verse is sensation. Neither the world is monotonous, nor the song. Neither the world is grey, nor the song.

Then we have the encounter of Šopov, the poet and the lake (1952). With the Lake of Life and Death. With the God of language. This is the time of the coded, hermetic speech. This is the time of the multiplied semantic mainstream. The Sphinx of poetry. Not a hole to peep through. A metaphor. A rebus. A riddle. Life and death, being and nonbeing become a recognisable theme that forms the key poetic world of Šopov, the shadow of death, birth seen as dying, and life as facing the irreversible. This apparently general philosophical world is transformed into specific poetic visualisations by Šopov, into linguistic images and figures, into symbols and harmonies, which can be illustrated with the image of daydreaming by the lake shore, with the numerous poeticised images of the lake, with the parables of the poem and poetry (‘The Song’, ‘The Poet and the Love’). The poem becomes the home of sorrow and joy, a poetic metathesis of the ambivalent sense for the home (language, tradition). The verse becomes a parable of existence, of being, of the essence. Verse is also a way of acting. Verse is a revelation. The verse is sensation. Neither the world is monotonous, nor the song. Neither the world is grey, nor the song.

Šopov makes a fast transition across the threshold of intimate lyricism, revealing the phenomenon of the beautiful in the nuances: of the body, nature, language and spirit. He discovers silence as a unity of the sensual and aesthetic, the emotional and sensory. He sustains and sings of his own melancholy, even in moments of supreme revelation and joy. The miniature poem, the quatrain ‘In Silence’, is the best example of this. We could add here the whole cycle of poems dedicated to the beauty (‘The Change’, ‘Ah, that Beauty’, ‘Towards the Seagull Circling Above My Head’, then ‘The Night’, ‘Leaf’, ‘By the Lake’, ‘Fishing by the Lake’). The following stage reveals the ethical dimension of the human being and represents a supplement to the image of beauty in yearning for Goodness and the Friend (‘We Should Be Better’). The Wind Carries Beautiful Weather (1957). The intimate confession is marked with the perception of humaneness, with ethical concepts. The warm remembrance of the poet is in search for a port, a shore where even time stops in the form of arabesque (‘Just Like All the Shores’). In this transitory stage, in this poetic transition, the poem is identified with the sky, with the Sky of Silence. Silence and speech are the two faces of the same medallion. The poem becomes less confessional and more discursive, a dramatic and poetic dialogue rises between the poetic subject and another, imaginary subject addressed by the poet. There is an illusion that the poem is neither intimate anymore, nor personal, even less autobiographical, although the poem cannot be fully liberated from these dimensions. The personal poetic perception becomes clearer, the need to announce that in poetry it is very important to preserve the way/form in which the confessional intimacy in the expression is realised: when it is direct, then it is pathetic and not poetic, when it is indirect and presented with images and other poetic constructive procedures, it is symbolic and poeticised.

Šopov makes a fast transition across the threshold of intimate lyricism, revealing the phenomenon of the beautiful in the nuances: of the body, nature, language and spirit. He discovers silence as a unity of the sensual and aesthetic, the emotional and sensory. He sustains and sings of his own melancholy, even in moments of supreme revelation and joy. The miniature poem, the quatrain ‘In Silence’, is the best example of this. We could add here the whole cycle of poems dedicated to the beauty (‘The Change’, ‘Ah, that Beauty’, ‘Towards the Seagull Circling Above My Head’, then ‘The Night’, ‘Leaf’, ‘By the Lake’, ‘Fishing by the Lake’). The following stage reveals the ethical dimension of the human being and represents a supplement to the image of beauty in yearning for Goodness and the Friend (‘We Should Be Better’). The Wind Carries Beautiful Weather (1957). The intimate confession is marked with the perception of humaneness, with ethical concepts. The warm remembrance of the poet is in search for a port, a shore where even time stops in the form of arabesque (‘Just Like All the Shores’). In this transitory stage, in this poetic transition, the poem is identified with the sky, with the Sky of Silence. Silence and speech are the two faces of the same medallion. The poem becomes less confessional and more discursive, a dramatic and poetic dialogue rises between the poetic subject and another, imaginary subject addressed by the poet. There is an illusion that the poem is neither intimate anymore, nor personal, even less autobiographical, although the poem cannot be fully liberated from these dimensions. The personal poetic perception becomes clearer, the need to announce that in poetry it is very important to preserve the way/form in which the confessional intimacy in the expression is realised: when it is direct, then it is pathetic and not poetic, when it is indirect and presented with images and other poetic constructive procedures, it is symbolic and poeticised.

The very frames of the poetic oeuvre which encompass the phase of lyrical intimacy, confession and subjectivism, define the image of modernist poetry, the Macedonian Modern. However, Šopov takes a step forward with the poems from his collection Nonbeing (1963). The Macedonian Modern enters the stage in the early 1960s. The canon of the lyrical Modern profiled by Aco Šopov is founded in the principle of the discourse of desire; on the pleading construed as a variation of the modified hymn-like singing typical of the archetype of lyricism (should we dare to envision it at all). Therefore, the Modern does not imply a radical disconnection from the intimist and confessional lyricism, practiced as intimately versified sermon, but continuation with the prayers of Nonbeing, and is there anything more intimate than praying? Šopov profiles the Macedonian Modern with his style that makes him feel sovereign: the devoutness, only this time the pleading discourse is in conflict with the powerful hermetic images of birth and death, with the images of the language and the human being, the woman and man. Instead of the sky of silence, this way becomes the diabolic sword of silence (‘Eight Prayer of My Body’). Finally, Šopov creates the poem masterpiece ‘The Word’s Nativity’, an immanent manifesto of the Macedonian neo-symbolism, or even better, supremacy. It moves along the edges of the ritualistic, magical word of the poem seen and pronounced as a prayer, and experienced as a ritualistic parable of birth and death. Such proximity between the ritual and the poem, between the codified poetic word and the codified word of ancient magic, is confirmed not only in the anthological cycle Nonbeing, but also in other poems that converge here: ‘Scar’, ‘There’s a Blood Down There’, ‘Despair Before the Fortress’ and ‘The Poem and the Years’. In Šopov’s poetry the bond between the blood and the poem is realised, as well as between the impetus and the word, between traumas and man’s memories, between peoples and humanity. This concept of poetic discourse, recognised as modernistic (anti-traditionalist, anti-social), universalises the topic of Šopov’s poetry, by allowing many meanings, difficult to demystify, overly semantic, heavy with significance, burdened with inherited and anticipated layers of existence. The Macedonian Modern, seen through the prism of Šopov and his poetry, practices a sort of hermetic discourse that enthralls and shocks, a condition that will pertain until a way is found, until the key for its decoding is found. This semiotic key is transient as much as the projections of the poetic meaning of the poems from Nonbeing are transient. This is a specific model of modernistic proteism. It is one of the major challenges of modern hermeneutics, since it is based on the principle of radicalisation of entropy, to an ultimate point whence once can see the pit, the absence of songs, the dubious world of nonbeing. The disappearing of everything that has been. The nonbeing. The semantic and ontological nonbeing of Šopov. This very Modern literature projects, from one to another, the blood and the meaning of being, it projects the known into the unknown, the conception into the end. The Macedonian Modern signed by Šopov sees birth and death as primordial dual concepts, as actualisation of the universal archetype in the Macedonian world in the space of the Macedonian language, in the time when this language had the right and freedom to scream from the bottom of the lungs. In this direction, Šopov encounters eternity: a dimension of time sought out by every poet.

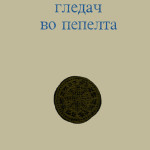

The peak of the Macedonian Modern, particularly the one promoted by Šopov is the poetry collection Reader of Ashes (1970) and the cycles Long Arrival of the Fire and Black Sun. In this collection the poetics radiate with awareness, there is the auto-poetic dimension of singing, there is awareness of the poetic dialogue with the universal worlds, regardless whether and to what extent they are taken from other authors and traditions (Black Sun for instance – Victor Hugo, the occult traditions). The fire and sun, earth, wind (air), water (lake, later ocean). The four elements of creation and existence of the universe, fire, water, earth, and air, so simple, and yet so difficult to shape poetically! Šopov begins with the elementary, in order to return to its beginnings, again, to the elementary, only this time with altered consciousness, with trails left behind, and a legacy for his people and his language. His world gets a name, just like his nonbeing, the non-world, which get the name Macedonia. Šopov manages to intercross the images of the universe with the images of Macedonia and see his own image reflected in it, as an inevitable necessity that emerged in the world in order to reveal the way that exists, however not with mute silence, but with poetic speech. We have no intention of interpreting this legacy of Šopov. It is too demanding to be done in this short foreword. Therefore, we are reminded that Macedonian poetry has indebted world culture with several of its poets, among which is undoubtedly Aco Šopov, who as one of the most prominent, and his poetry book Reader of Ashes is one of the most significant.

The peak of the Macedonian Modern, particularly the one promoted by Šopov is the poetry collection Reader of Ashes (1970) and the cycles Long Arrival of the Fire and Black Sun. In this collection the poetics radiate with awareness, there is the auto-poetic dimension of singing, there is awareness of the poetic dialogue with the universal worlds, regardless whether and to what extent they are taken from other authors and traditions (Black Sun for instance – Victor Hugo, the occult traditions). The fire and sun, earth, wind (air), water (lake, later ocean). The four elements of creation and existence of the universe, fire, water, earth, and air, so simple, and yet so difficult to shape poetically! Šopov begins with the elementary, in order to return to its beginnings, again, to the elementary, only this time with altered consciousness, with trails left behind, and a legacy for his people and his language. His world gets a name, just like his nonbeing, the non-world, which get the name Macedonia. Šopov manages to intercross the images of the universe with the images of Macedonia and see his own image reflected in it, as an inevitable necessity that emerged in the world in order to reveal the way that exists, however not with mute silence, but with poetic speech. We have no intention of interpreting this legacy of Šopov. It is too demanding to be done in this short foreword. Therefore, we are reminded that Macedonian poetry has indebted world culture with several of its poets, among which is undoubtedly Aco Šopov, who as one of the most prominent, and his poetry book Reader of Ashes is one of the most significant.

After this threshold in the evolution of contemporary Macedonian poetry, Šopov was able to rest a while and return to the canon of the mild, contemplative and intimately intoned speech of admiration and recognition of the similarities in the world/language. In this phase Šopov was able to surrender to the impulses of experiencing the unknown world, the world of Black Africa, the Black Woman, the music of the baobab, rainy seasons, the lavishness of the flamboyant, and pout in it the gained experience, the wisdom of the mature personality, the rootedness in the world as a poet. This tendency frames his poetic adventure, his pilgrimage across the pathways of the imaginary, the fantasies and drives, the promotions and ritualistic accords and rhythms. Šopov recognises himself in the rhythms of African music, initially present in the rhythms of his couplets from The Long Arrival of the Fire, for instance. In this recognition of similarities we can recognise the differences between Africa and Macedonia. There are similarities and differences between the worlds, but on different planes.

After this threshold in the evolution of contemporary Macedonian poetry, Šopov was able to rest a while and return to the canon of the mild, contemplative and intimately intoned speech of admiration and recognition of the similarities in the world/language. In this phase Šopov was able to surrender to the impulses of experiencing the unknown world, the world of Black Africa, the Black Woman, the music of the baobab, rainy seasons, the lavishness of the flamboyant, and pout in it the gained experience, the wisdom of the mature personality, the rootedness in the world as a poet. This tendency frames his poetic adventure, his pilgrimage across the pathways of the imaginary, the fantasies and drives, the promotions and ritualistic accords and rhythms. Šopov recognises himself in the rhythms of African music, initially present in the rhythms of his couplets from The Long Arrival of the Fire, for instance. In this recognition of similarities we can recognise the differences between Africa and Macedonia. There are similarities and differences between the worlds, but on different planes.

Finally, the poetic lake of Šopov has its tides, and goes through a state of withdrawal into an inner rendering of imagery. Šopov’s poetry is hushed, both semantically and stylistically, in his final poetry book Tree on the Hill (1980). Šopov approaches his end. He is weary. Melancholic. Alone before the encounter with the Supreme. In such a state of the spirit, he returns to all the important themes: the theme of flame/fire, body, light (sun, lightning), earth and native land (‘Shara’, ‘Tree on the Hill’), wind/storm and lake/water. The lake of life. In his last poem he states: “Macedonia is the world’s fate, the world is Macedonia’s fate.” (‘A Journey to the Native Land – Reunion with the World’). I have neither arguments, nor willingness to claim that he knew what was going to happen with his beloved Macedonia only twenty years after his death. However, I believe he could anticipate it. In fact, in one of his final poems, he announces the concern with one image of Macedonia, which can be easily interpreted and understood: “Shaken by tempests and pains of labour/ the galleon sails through the tempests/ and disappears amidst the waves/ and then emerges from beyond them/ with the name Macedonia”. (‘Lake of Life’)

Finally, the poetic lake of Šopov has its tides, and goes through a state of withdrawal into an inner rendering of imagery. Šopov’s poetry is hushed, both semantically and stylistically, in his final poetry book Tree on the Hill (1980). Šopov approaches his end. He is weary. Melancholic. Alone before the encounter with the Supreme. In such a state of the spirit, he returns to all the important themes: the theme of flame/fire, body, light (sun, lightning), earth and native land (‘Shara’, ‘Tree on the Hill’), wind/storm and lake/water. The lake of life. In his last poem he states: “Macedonia is the world’s fate, the world is Macedonia’s fate.” (‘A Journey to the Native Land – Reunion with the World’). I have neither arguments, nor willingness to claim that he knew what was going to happen with his beloved Macedonia only twenty years after his death. However, I believe he could anticipate it. In fact, in one of his final poems, he announces the concern with one image of Macedonia, which can be easily interpreted and understood: “Shaken by tempests and pains of labour/ the galleon sails through the tempests/ and disappears amidst the waves/ and then emerges from beyond them/ with the name Macedonia”. (‘Lake of Life’)

I believe that Aco Šopov’s poetry book entitled Nonbeing was not created by accident, just at the time when Macedonian literature and Macedonian culture are going through their expansion and bloom, which was very rare in the past. I believe that Aco Šopov has made close contact with his time through his poetic word. His poetry can actually be defined as an encounter with the time that the poet recognises as his own, and the time that recognises him as its own. We should most likely interpret the meaning of his expression from the conversation with his daughter, Jasmina Šopova: “ That search for the word is the poet’s need to approach his own time. This is where all troubles and all beauties of the poetic work come from.” (2003,125) Šopov approached his own time to that extent, which will challenge future generations to solve the riddle of his time from the metaphors we now have as Aco Šopov’s legacy: the metaphor of nonbeing, the black sun, and the word’s nativity.

*A foreword to Aco Šopov’s poetry selection The Word’s Nativity by Kata Ćulafkova (in Macédonien, in 2008, and in English, in 2011).

Translated from Macedonian by Perica Sardžoski