This post is also available in: Macedonian

A lively and pregnant imagery*

By Graham Reid

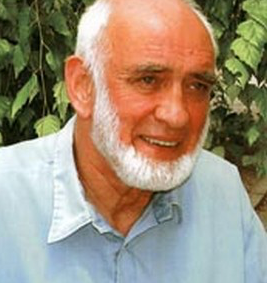

Aco Šopov is one of the most important Macedonian poets. He was born on 20 December 1923 in Stip, in eastern Macedonia, where he attended both primary and secondary school. Influenced by his mother, a schoolteacher who herself wrote love lyrics, Šopov’s poetic debut took the form of writing for a wall newspaper in his high school. Various societies there provided a focus for people of a literary bent, and to one of these, Vančo Prke — himself a budding poet strongly influenced by Miroslav Krleža — Šopov showed his first notebooks containing poems inspired by current events. As a young man caught up in the enthusiasm of a revolutionary situation, Šopov wrote his first poems in social protest, as a revolt against injustice.

On the eve of Yugoslavia’s involvement in World War II, which began in 1941, Šopov wrote the poem “Anovite” (Inns), describing the fate of the last soldiers to be drafted into the army of prewar Yugoslavia. Soon engaged in the partisan resistance to the Nazi occupying forces, he continued writing poetry in the lulls between fighting. Such are the poems “Ljubov” (Love), written in his army notebook immediately after an engagement, and “Partizanska prolet” (Partisan Spring) written during an attack on the town of Kratovo. These first poems showed Šopov to be a highly personal poet even when he was chronicling events of a social or patriotic nature. They showed a lyrical individuality and an autobiographical intimacy. He found his subject matter in his own experience, as when writing of a much-loved woman who was a fellow partisan, and yet he succeeded in avoiding too great a preoccupation with the self and the clichés of a falsely sentimental intimacy. In the same way his poems of social protest avoid the cheap and easy use of the slogans and catch phrases that were then in vogue.

Šopov ‘s poetry of this period, closely bound with his own experience of a war of national liberation, serves to illustrate his rejection, from the outset, of a utilitarian style with a narrow social or political purpose. This is not to say that these poems do not have a clear message. They treat the horrors of war, the traumas of a people finding itself, and the youthful awakening of consciousness throughout society, and they embody a vision of the future. Treating also the themes of love, struggle, and death, and employing imagery that conjures up an apocalyptic atmosphere, they also have overtones from folk poetry. Defiant and often action packed, they convey deep feeling and contain striking passages and images; nevertheless, these poems, published as Pesni (Poems) in Belgrade and Kumanovo in 1944 and in Stip the following year, are primarily of historical interest.

After the war Šopov graduated in philosophy from the University of Skopje and began work in the public sector. He had already been involved editorially in the youth publication Ogin (Fire) and from 1947 on was engaged in various literary undertakings: he founded the journal Idnina (Future) and at various times worked as editor of Nov den (New Day), Sovremenost (Contemporaneity) and Horizont (Horizon) and the satiric magazine Osten (Spur), to all of which he also contributed poems and translations. He then became director of the Makedonska kniga publishing house. His next three books of poetry, Pruga na mladosta (The Youth’s Railroad) (written with Slavko Janevski, 1947), Na Gramos (On Gramos, 1950), and So naši race (With Our Hands, 1950) developed the themes of his earlier poems and were a further organization of his experience of revolution and national liberation.

With Stihovi za makata i radosta (Verses of Sorrow and Joy, 1952) and Slej se so tišinata (Merge with Silence, 1955) there came a turning point in Šopov’s poetry and conceivably in Macedonian poetry at large. Consistently writing out of individual experience, Šopov now began to address his readers as individuals rather than as collectivized humankind. These largely confessional lyrics on romantic lines are poems of feelings, sensuous evocations permeated by the emotions of resignation, pain, sorrow, weariness, parting, and melancholy, while yet retaining a belief in human values. Šopov was writing affirmatively of beauty, love, and freedom in this transitional phase while also acknowledging the existence of ugliness, hatred, and slavery. In his third phase, that of the award-winning collection Vetrot nosi ubavo vreme (Winds Bring Nice Weather, 1957), Šopov was engaged in delving as deeply as possible in search of himself, and the resulting poetry was often tinged with a dark melancholy.

The periods of Šopov’s poetry are not hermetically self-contained. What distinguishes them is a marked development at each stage in both range and complexity, with no loss of directness and with an increasingly sophisticated simplicity. If, overall, his first phase was one of a movement from the general to the personal and the second phase is marked by writing of a personal nature, the line of his third phase moves from the personal to the universal. These poems present the subject of love as their starting point and project a view of the world and its phenomena as essentially transitory. They present a more complex reality than his previous work, uncovering in the depths of the author’s own being that nonbeing that threatens everyone and everything and that constantly hovers in the atmosphere of a world where unrest is unending. No longer either exclamatory or purely confessional, these poems are meditations on an unbeing that emerges not from unbeing as a transcendental system of ideas but from the poet’s own experience and his feelings toward the world he inhabits. In these poems of love with a cosmic dimension Šopov employs a wealth of symbols and ideas, finding a place for intellectual experience as well.

The existential questions posed in the poems in Nebidnina (Unbeing, 1963) are developed in the next two collections, Gledač vo pepelta (Reader of the Ashes, 1970) and Pesna na crnata zena (The Black Woman’s Song, 1976), written out of the experience of the years 1971 to 1975, when Šopov was the Yugoslav ambassador to Senegal. There is a fusion of content and spirit in a form that allows a certain ambiguity; the formal elements of rhythm and versification are not added decoration but are integral to the whole structure of the poetry as an organizing principle. The author’s main concern here is the conflict between humanity and the nature of existence and a resolution of that conflict. He achieves this resolution through the metaphors that extend throughout these three collections. As a proven craftsman, he presents his own experience of life together with the wider drama of human destiny in a reflective synthesis that reaches out to the limits of existence and occasionally to the realm of the absurd. The confessional element is still found in these poems, but it has been rigorously refined. The verse is disciplined, highly organized, and taut, as he carries on an unsparing and at times terrible dialogue with himself, with his poetry, and with literature in general in a world that is often chaotic and indeed verges on the incomprehensible.

In Šopov’s later writing unbeing came to represent not only the tragic aspect of human nature but also a Promethean heroism, a Faustian exhilaration, a torch of Heraclitean fire burning in humankind and after and beyond an individual’s life. However fleeting human life, however tragic the history of the black peoples of Africa, however isolated the experiences of loss, sickness, and death, humankind is involved in an unceasing struggle through understanding to overcome transience, death, and nothingness. Šopov sees the transcendence of these conditions as a reconciliation of darkness with light, of unbeing with love, of mutability with lastingness, and of life with poetry. Thus, an individual’s life and all upon which one has left his mark are transformed into symbols and memories that outlast him.

This is the substance of the poems of the poet’s last book, Drvo na ridot (A Tree on a Bare Hill, 1980), and those included in the selection Luzna (Scar, 1980). In these poems Šopov achieves a coherent construction with no redundant word or image and a lively and pregnant imagery that binds together the experience of the author and the reader. The language of these poems is penetrating, resonant, and melodic. Poetry is the tool with which the author explores life’s mystery, whether this suffuses the beauty of Africa despite the shadow cast by slavery, the lone tree in a bare Macedonian landscape, or the reflections of a clochard in a Paris hospital.

From his earliest work Šopov speaks with his own voice, but his voice developed and was refined in part through his work as a translator. Working mainly from Serbo-Croatian, Russian, and French, he translated into Macedonian, over a period of twenty years, an impressive list of world classics by authors including Pierre Corneille, Edmond Rostand, William Shakespeare (Hamlet, 1960, and Sonnets, 1970), Miroslav Krleža, Jovan Jovanović-Zmaj, Izet Sarajlić, and Dragutin Tadijanovic. In turn, his poems have been translated into many languages, including English.

After a long illness Šopov died in Skopje on 20 April 1982.

__________________

* Published in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. ©2005-2006 Thomson Gale

Copyright Information

Graham W. Reid, University of Skopje. Dictionary of Literary Biography. ©2005-2006 Thomson Gale, a part of the Thomson Corporation. All rights reserved.

©2000-2013 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

British philologist Graham W. Reid (1938–2015) taught English for twenty-five years at Cyril and Methodius University, in Skopje. In 1973 he and his wife, Peggy Reid, received the Struga Poetry Festival Translation Prize for The Sirdar by Grigor Prlicev.